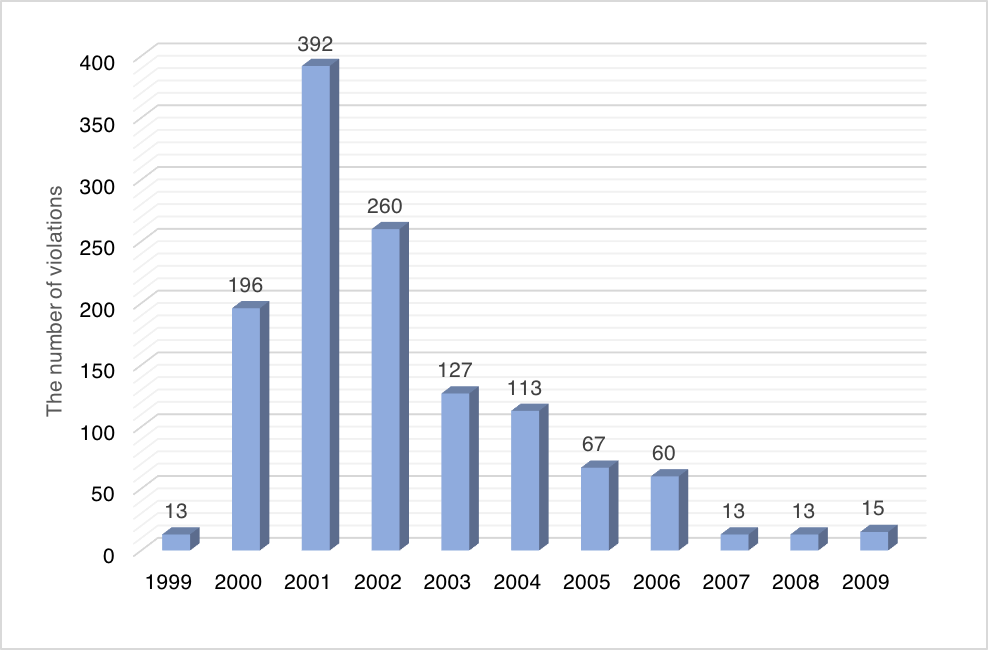

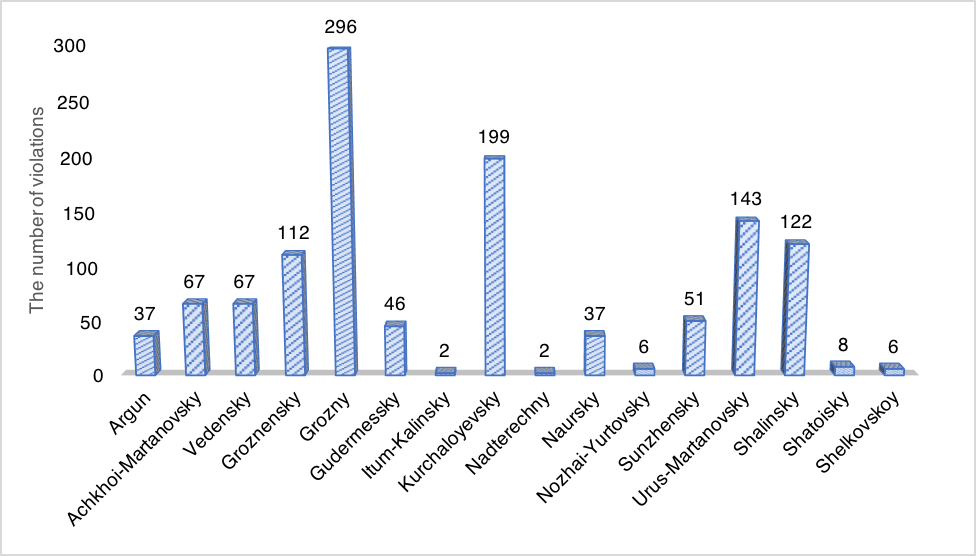

The Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center Database (hereinafter the Database) encompasses 32,297 documents containing information about the situation in the entire North Caucasus region – including Ingushetia, North Ossetia and other republics – between 1992-2018. Overall, 22,180 documents in the Database concern the counter-terrorist operation in the Chechen Republic. The majority of these documents (20,887) contain information about the incidents which took place between 1999-2009, namely the active phase of the counter-terrorist operation in the Chechen Republic.

The Database is unique in that it accumulates materials from public sources (mass media, the Internet, books) as well as those collected by employees of well-known human rights organizations (diaries, photographs, procedural documents).

For instance, the Memorial Human Rights Centre (hereinafter the Memorial) is one of the largest information sources for the Database. This organization has published 16,235 documents. The materials of the Memorial cover the periods of both the first and second Chechen conflicts, as well as the post-war era. The scope of materials collected by the Memorial is broad. They include descriptions of the killings, kidnappings and disappearances of citizens, as well as special operations carried out in settlements with the use of military equipment, including the shelling and bombardment of cities and villages, and destruction of private property.

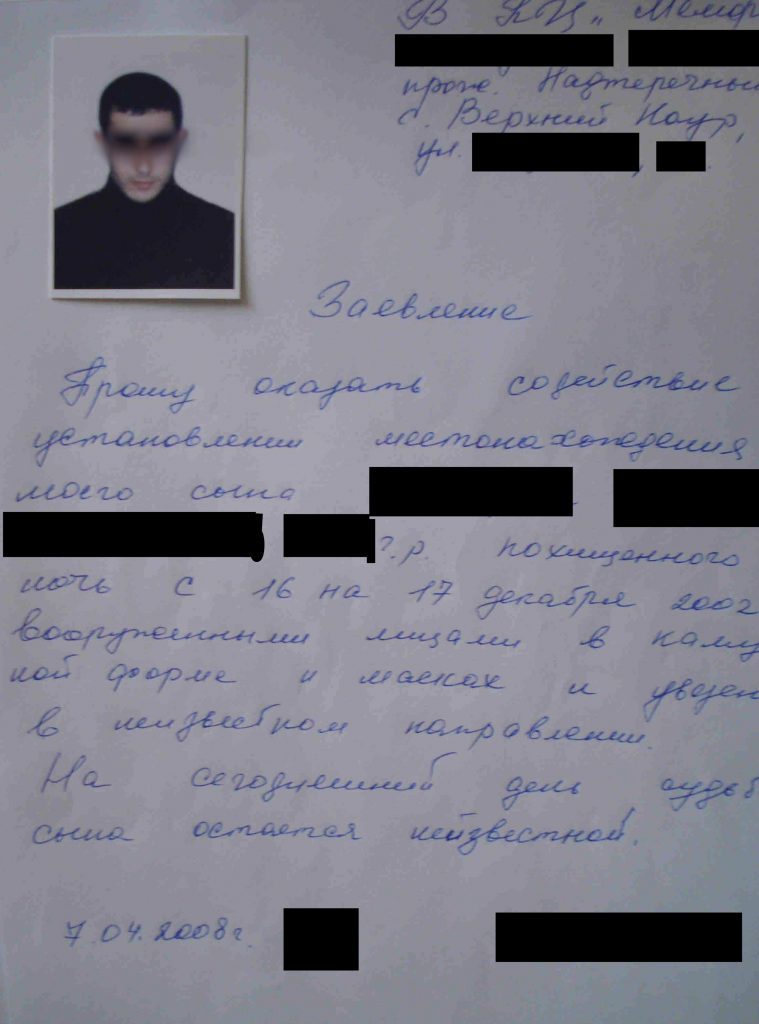

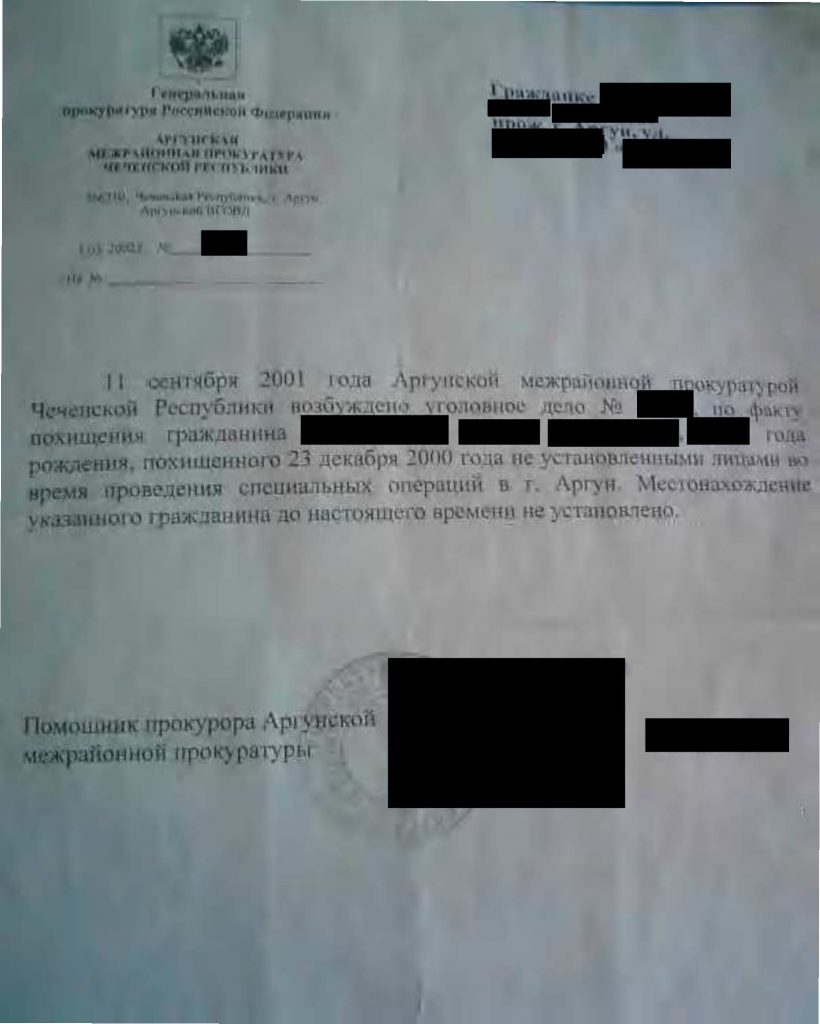

Furthermore, the organization has collected an extensive amount of materials with information on missing persons, including transcripts of interviews with the relatives of missing persons which have exposed details of the circumstances surrounding the kidnappings, and the state bodies to which they have subsequently applied with regard to the violations. Where possible, relatives have also submitted correspondence with law enforcement agencies, as well as photographs of the disappeared victims, to the Memorial, which have subsequently been registered and stored in the Database. Additionally, relatives of missing persons have allowed the Memorial staff to take photographs of passports, military tickets and other documents connected to the victims of the conflict. These documents have also been stored in the Database and linked to corresponding victims’ profiles.

The Russian-Chechen Friendship Society (RCFS) has also publicized a significant number of documents which has allowed for the systematization of the chronology of the military conflict. The type and subject-matter of the materials from the RCFS vary, with press releases making up 1,680 of the total 3,039 documents, and articles, photos, books etc. forming the remainder.

| Information Donors | Number and Type of Materials | Content Description |

| “Mothers of Chechnya” | 26 publicly available lists | 334 names of the disappeared men and women during the first Chechen war (1994-1996) |

| Chechen Committee for National Salvation | 1,798 publicized press-releases and articles | Topics predominantly address the difficulties experienced by internally displaced persons, covering the periods of the first and second Chechen wars |

| Interregional Committee against Torture | 180 publicized official documents | Procedural documents: citizen complaints and applications to law enforcement agencies; powers of attorney; notifications; responses from various authorities (e.g. from the Prosecutor General’s Office of the Russian Federation or from the Presidential Administration) |

| Human rights activists A. Mnatsakanian and Kh. Saratova | 1 document communicated to other NGOs | 608 names of people who have disappeared under various circumstances, such as kidnappings from houses, disappearances during the course of sweeping operations (zachistkas) of settlements etc. |

| Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Chechen Republic | 7 lists published on websites of official bodies | 760 names of employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Chechen Republic who have either died during hostilities, died as a result of diseases, as well or died as a result of road accidents between 2001-2007 |

| Commissioner for Human Rights in the Chechen Republic | 77 publicized lists | 3,211 names of disappeared people during the first and second Chechen wars between 1994-2009 |

| Human Rights Watch | 494 documents | The materials are presented in the form of press releases (213 documents), articles and reports covering the details of bombings of settlements in Chechnya (zachistkas). A number of materials focus on the topic of internally displaced persons in the Chechen Republic and Ingushetia e.g. life in temporary camps, daily problems faced etc. |

| European Court of Human Rights | 250 judgments (obtained through HUDOC) | 2,534 names of victims of killings, kidnappings, torture, mine explosions, and lootings of property, as a result of which relatives have lodged a complaint with the European Court of Human Rights |

| Norwegian Helsinki Committee | 219 documents | Articles covering the periods of conflict in the Chechen Republic between 1994-2009, addressing in particular the activities of affected journalists in the North Caucasus. Some of the materials presented are videos (from October to December 1999) which demonstrate the destruction caused as a result of bombings and shelling of Chechen settlements |

The majority of the documents are in Russian (20,865) and the remainder are in English.

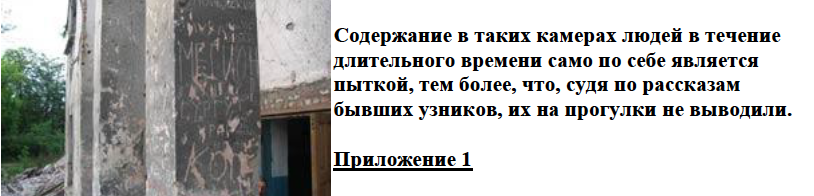

The Database also stores 490 images depicting various consequences of the conflict. This includes images of disappeared people and their relatives; individual and mass graves; corpses found displaying signs of severe torture; destruction of houses and other property; and public demonstrations and rallies.

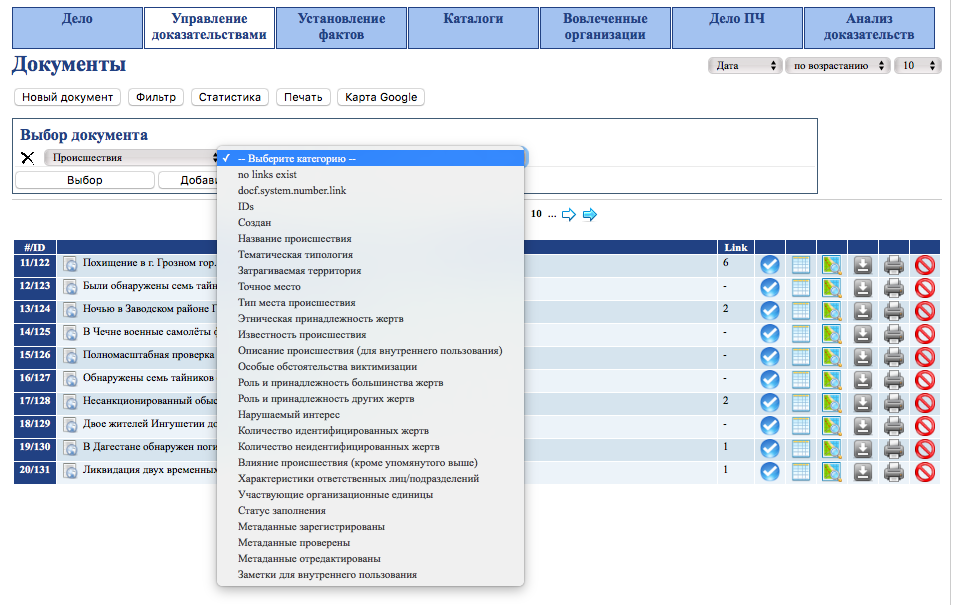

Materials stored in the Database can be divided into the following groups:

The first group includes documents in the form of profiles of disappeared people which have been created on the basis of testimonies provided by relatives. Such materials contain detailed personal data of the victim, information about the circumstances of the violation, and measures taken by the family or state bodies to find their whereabouts.

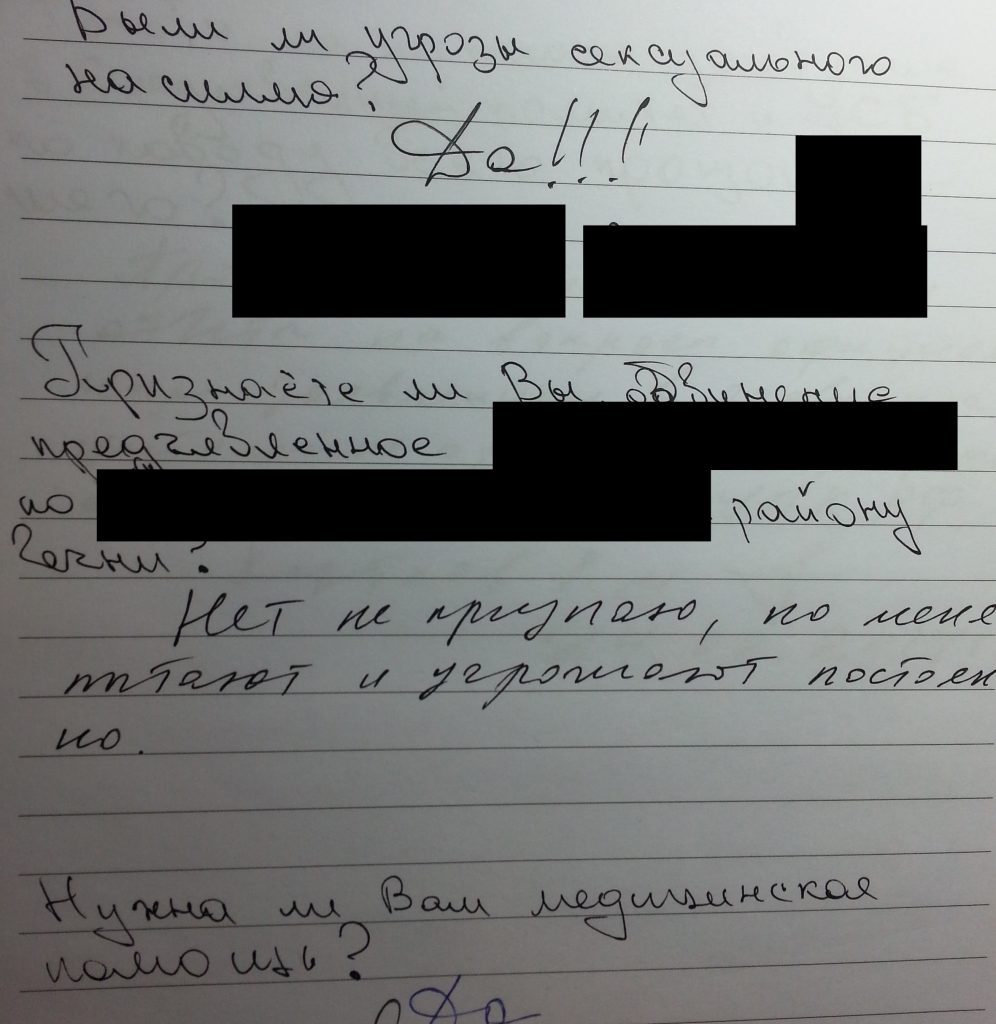

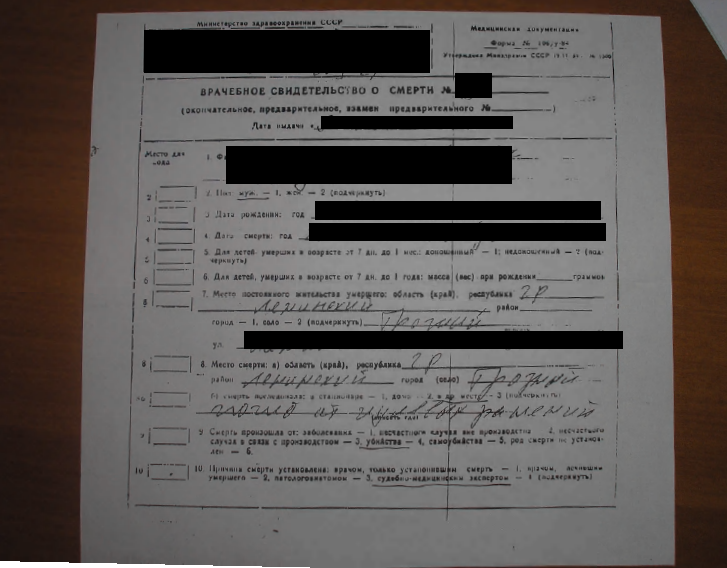

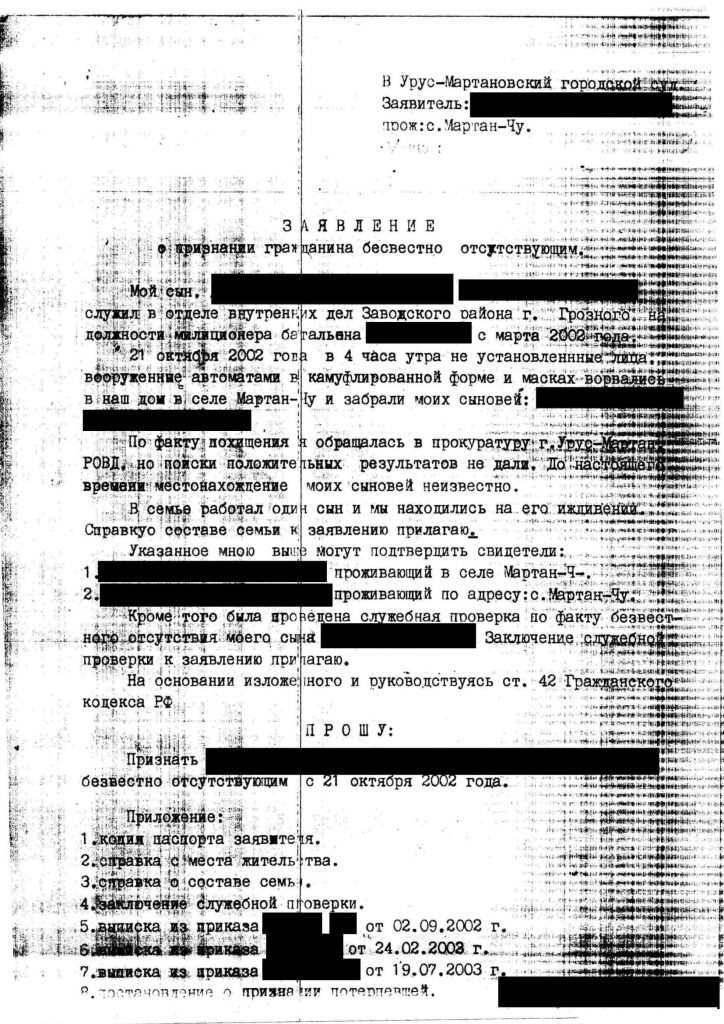

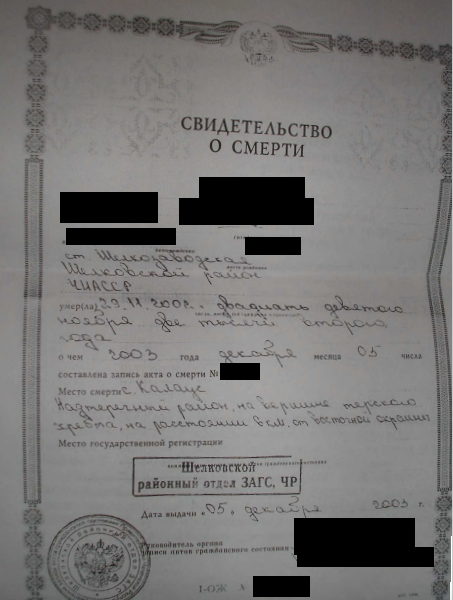

The second group consists of procedural documents provided by relatives of the disappeared people. These include in particular: interrogation statements from those who have been granted victim status; witness statements; examination reports from the scene of the crime and reports of other investigative actions taken; and decisions relating to the granting of victim statuses, the suspension of criminal cases, as well as rulings of courts of different instances, such as declaring a disappeared person to be legally deceased. Relatives have retained these procedural materials in the hope of finding those missing who have become trapped in the war and have disappeared without a trace.

The third group accumulates eyewitness accounts of the bombings and shelling of settlements (zachistkas), life in camps for internally displaced persons, and the difficulties experienced by individuals once they returned back home to the Chechen Republic following the termination of war hostilities in some regions. This group of documents also includes applications submitted by relatives to human rights organizations requesting assistance in ascertaining the whereabouts of the disappeared people.

Each information source is used to create and search profiles of each victim in the Database. Each name mentioned in the materials was individually registered in the Database. The Database also gives the possibility to create different status profiles of an individual. For example, the same individual could be a victim in one incident, and a witness in another. This allows for a more structured understanding of the conflict and the ability to identify all existing connections between different people. For some individuals, several profiles can be registered in the Database with different information donors (for example, from the Memorial and from the ECtHR). This is especially true for victims of large-scale bombings or special operations, which attracted the attention of many human rights and international organizations.

For example, information about the killing of 18-year-old Elza Kungaeva by former Colonel Yury Budanov in 2000,[1] was recorded by the Memorial, the RCFS and the Committee of National Salvation. Therefore, three profiles of E. Kungayeva are registered in the Database. Each of these profiles contains information that was obtained by each separate organization.

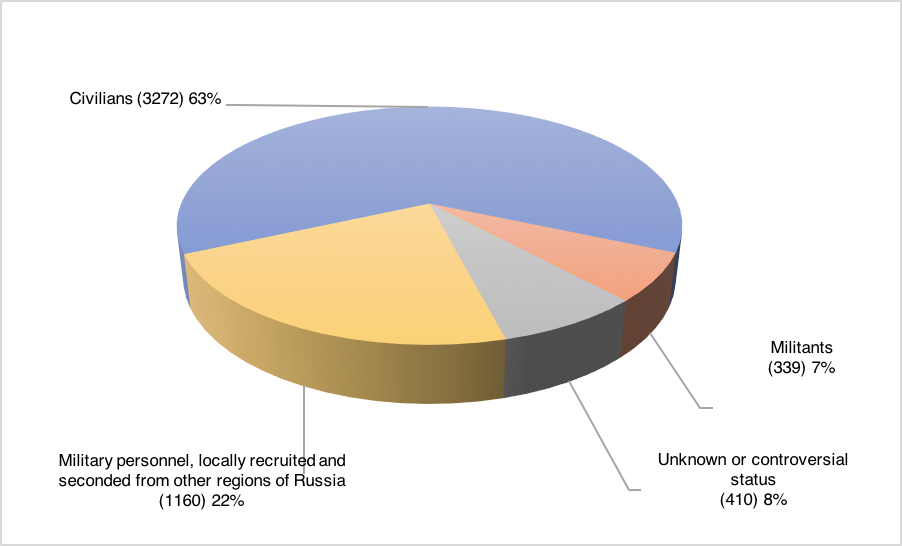

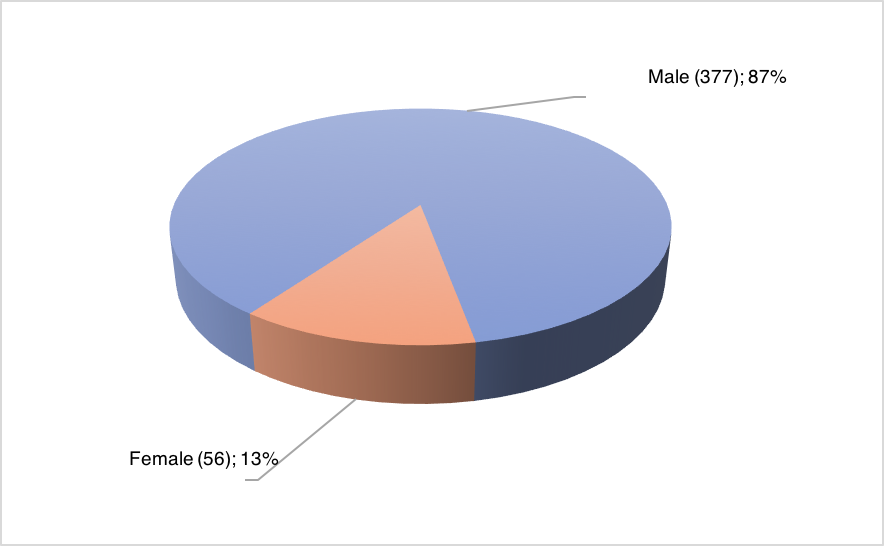

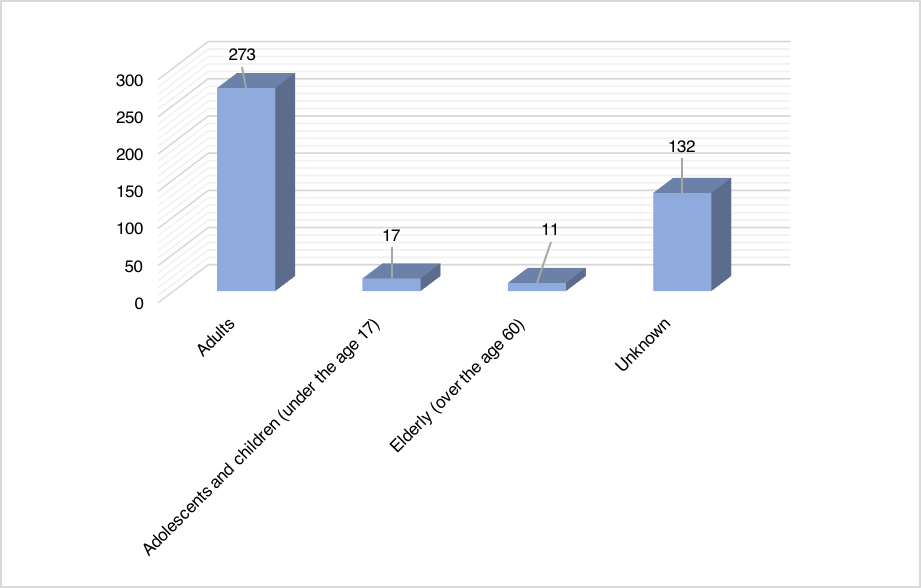

Due to this method, there are currently a total of 38,825 victims, who suffered in the Chechen Republic during the conflict, registered in the Database. However, this may not be reflective of the actual number of victims of the conflict.

The analysis of all materials has allowed for the collection of the most accurate information relating to each victim and violation. Each victim is analyzed using all of the collected documents and a single verified profile is created based on all source-profiles. All corresponding information available from the information donors is indicated in this single verified profile. In some cases, different sources may contain contradictory information – for example, conflicting information may be provided regarding the date or circumstances of the violation. In such cases, the information is either directly verified and confirmed with the sources, or if not possible, the discrepancies in the data are indicated in the profile.

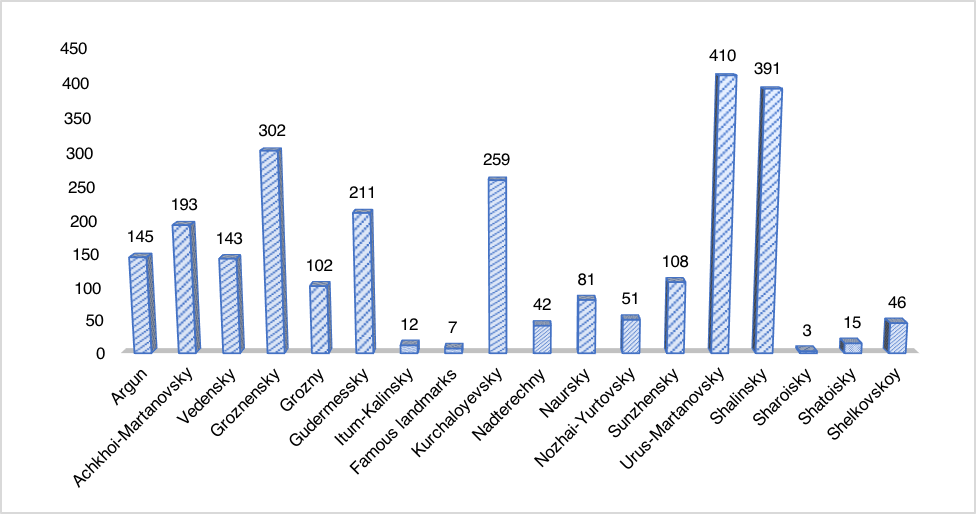

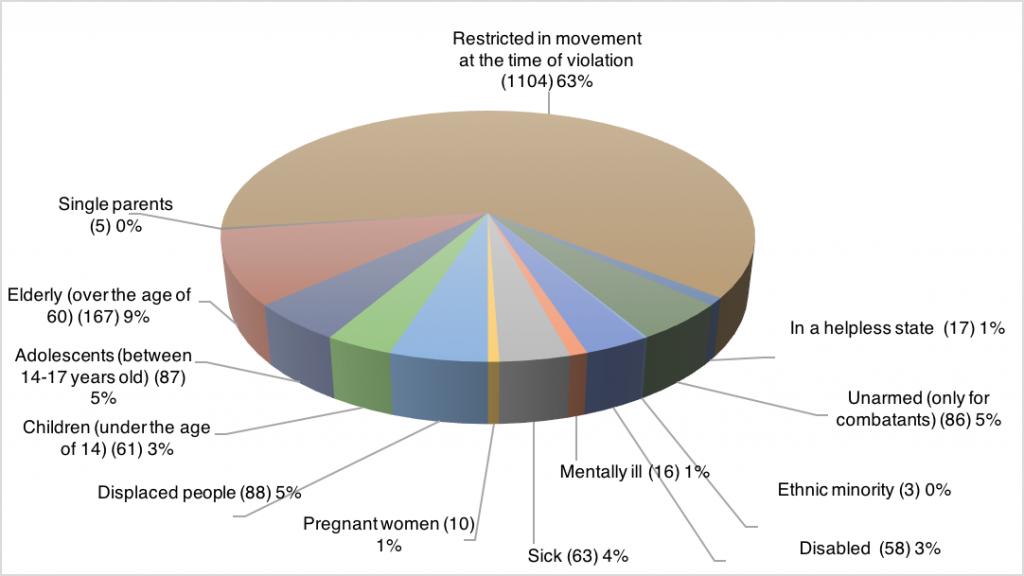

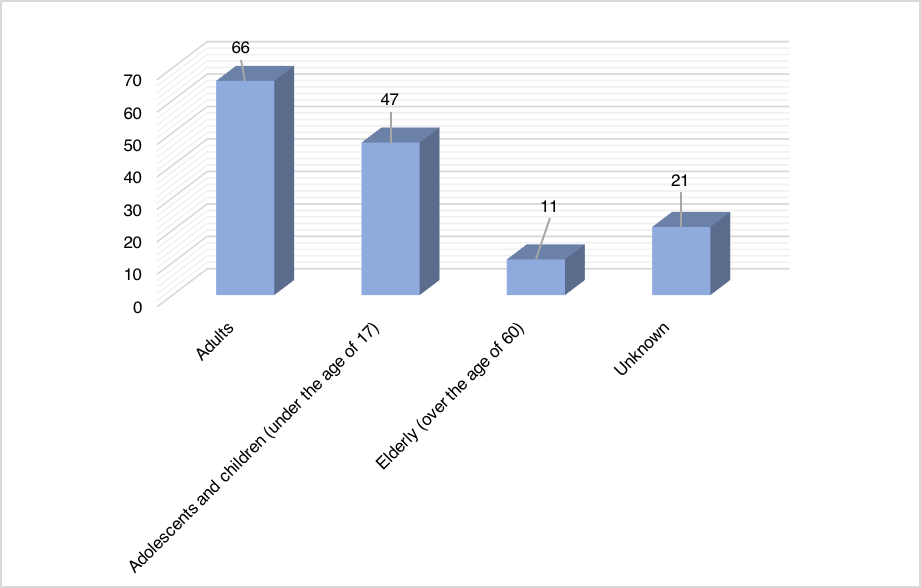

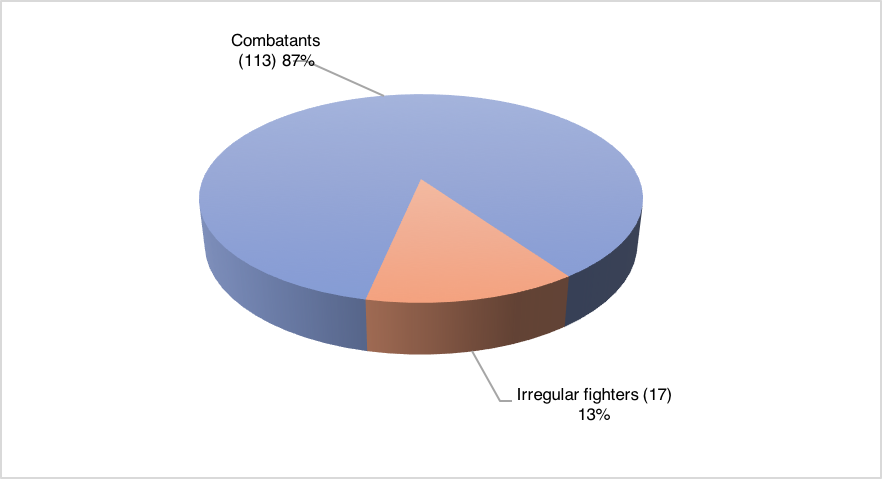

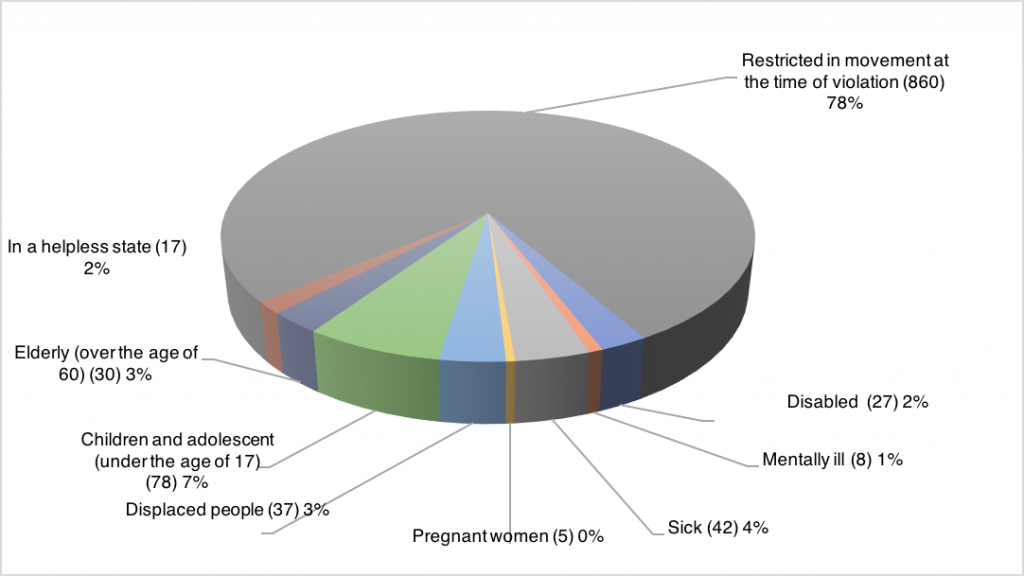

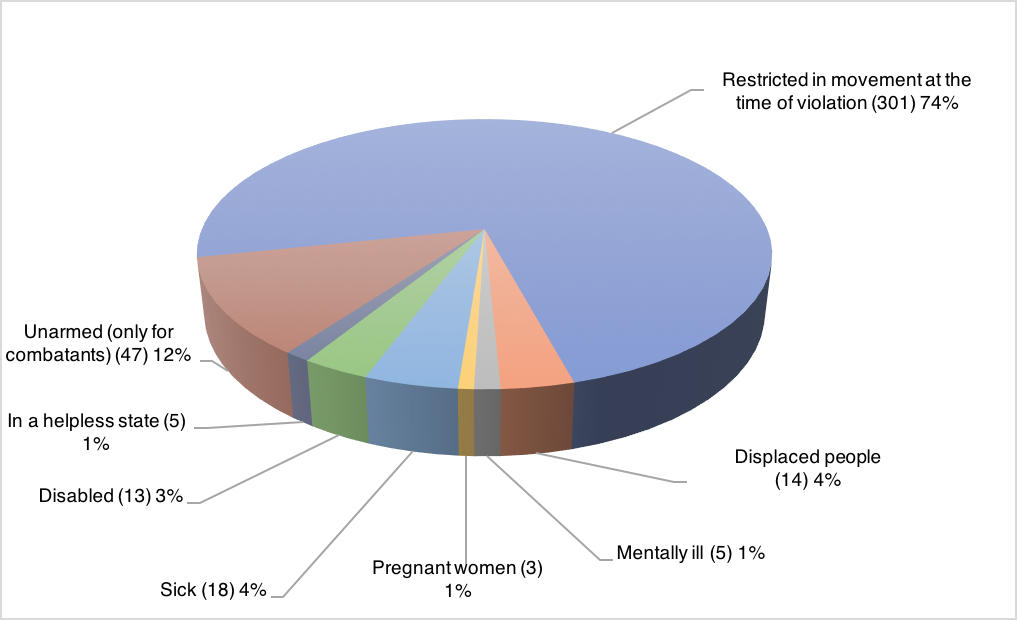

Through this verification process, 16,633 unique profiles have been created for each victim from 38,825 source-profiles. Each profile contains the most accurate data relating to the victim, such as the victim’s health status, profession, distinctive features and the place of burial, information relating to the violation (date and place of the violation, circumstances, factors that caused the violation, status under humanitarian law), and the outcomes of complaints to national authorities, human rights organizations and the ECtHR.

It should be noted that the Database not only contains the profiles of those whose names were identified but also those whose first and last names could not be established. Such victims, both individuals and groups of individuals, were registered collectively as nameless victims, with currently 1,642 such profiles. Accordingly, these are groups of individuals ranging from two to 50 people, depending on the information provided. Such victims were registered, for example, in the following way: “Four young people from the village of Novye Aldy detained on June 4, 2006”. Nameless individual victims were registered in a similar manner: “A young teacher killed as a result of a mine explosion in a village. Chiri-Yurt, October 2000”. Profiles of nameless victims were created with sufficient to register a profile and specific information about the victim and the violation. Due to the absence of any individualized information, however, they are deemed to be unsuitable for the verification process and are therefore not included in the number of victims when generating statistics on the victims of the war in the Chechen Republic.

This integrated and comprehensive approach to documentation in the Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center Database has allowed for the creation of the most accurate picture of the conflict in the North Caucasus.

The relevant statistics were updated on 26 March 2019.

The data is subject to change in view of the ongoing work by the Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center on the search and identification of victims of the armed conflict.

Media library

Project analyst at his work in NEDC database

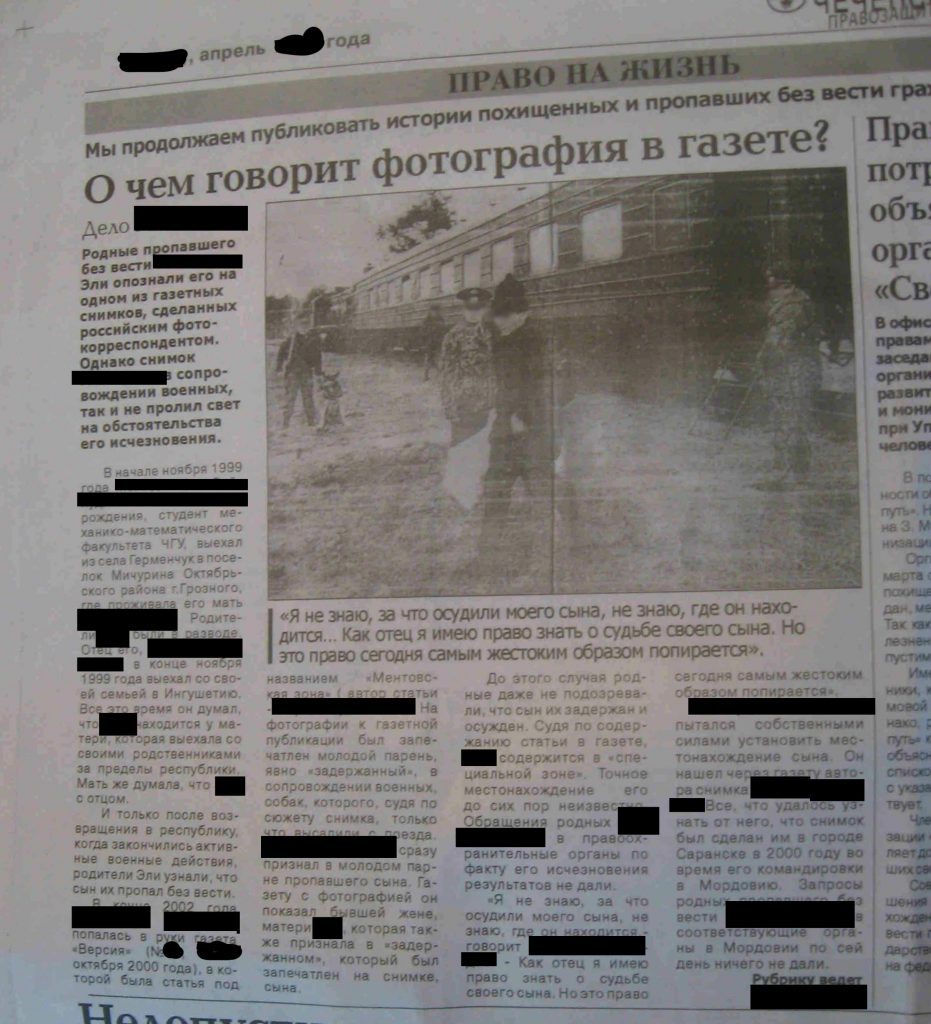

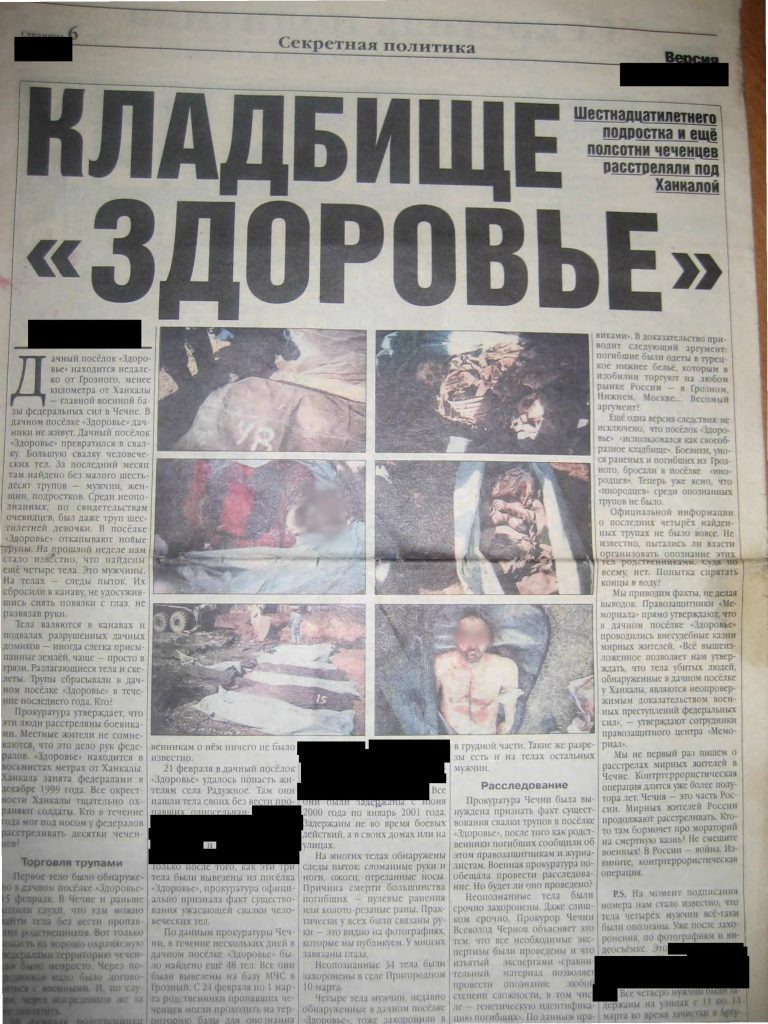

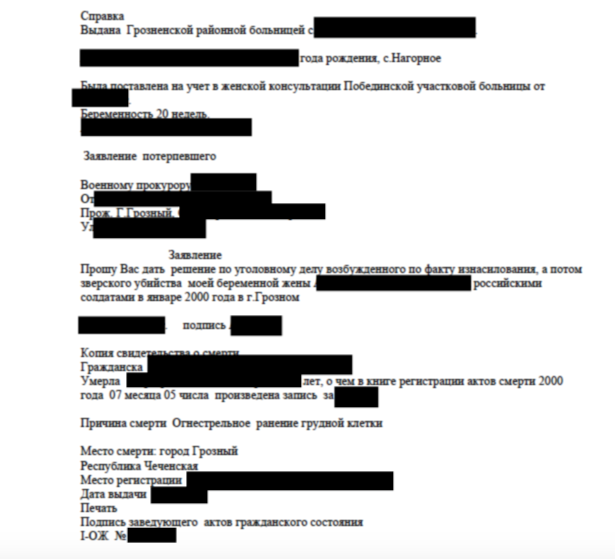

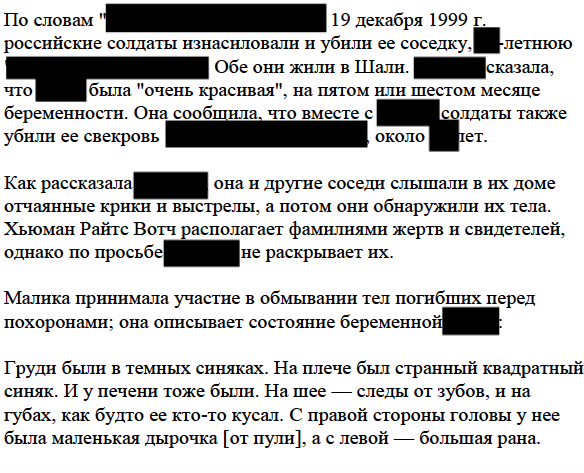

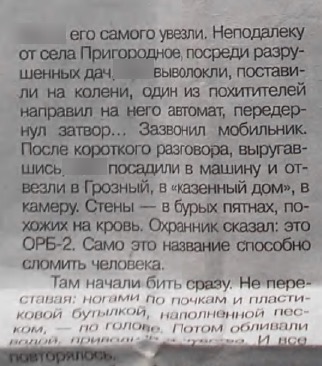

NEDC document 26558

NEDC document 26983

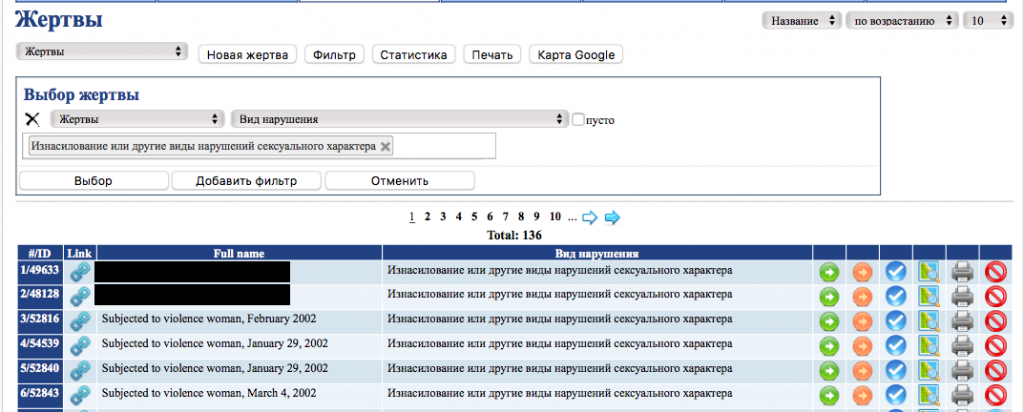

NEDC document 9839

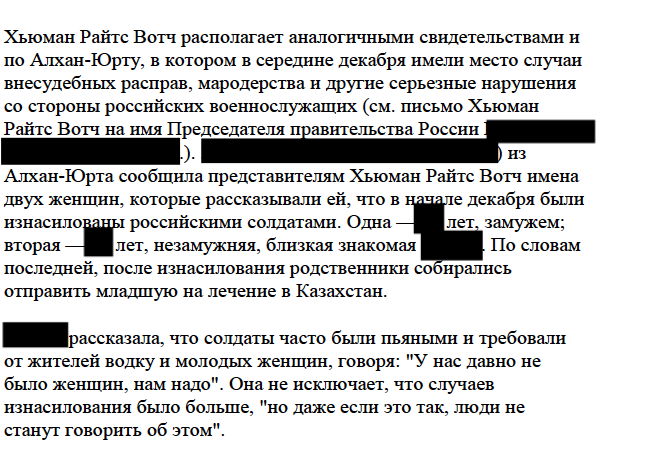

NEDC document 25716

NEDC database

References

[1]RIA Novosti, “The killing point in the case of Elza Kungaeva”, June 10, 2011, https://ria.ru/20110610/386794477.html.